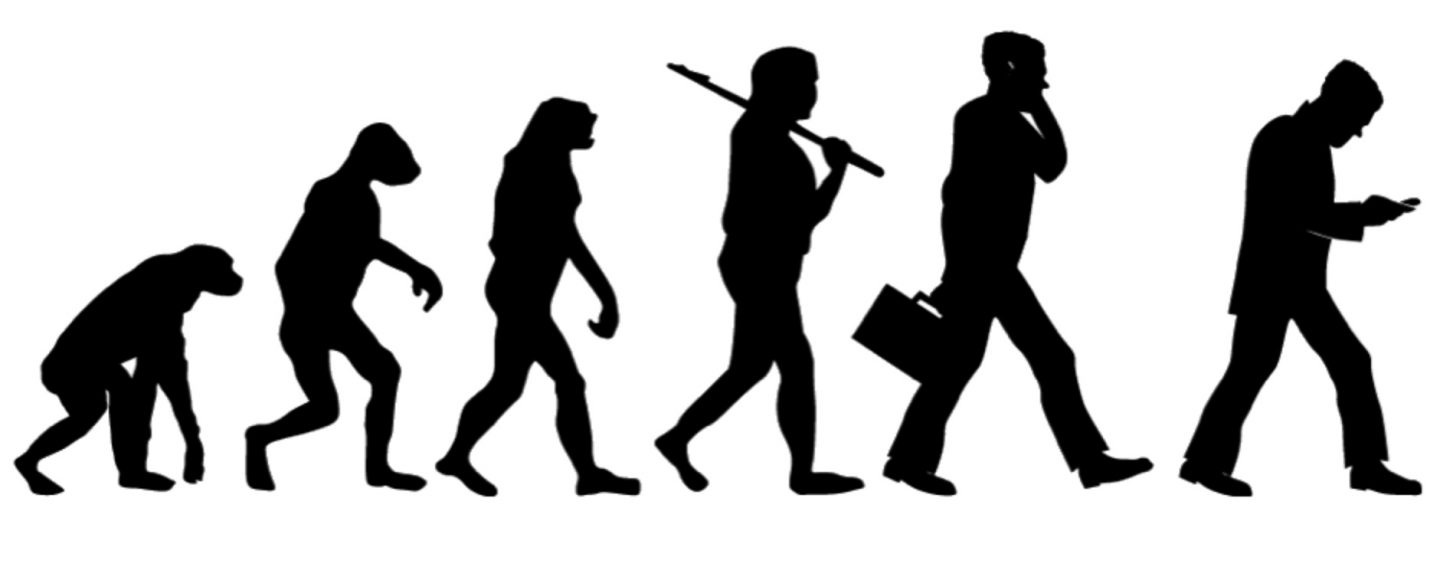

Last year Justice Abella, from the Supreme Court of Canada, gave a talk at Thompson Rivers University’s (TRU) law school. During the talk, she commented on how slow the practice of law is at evolving. She presented the analogy that if we were to take a surgeon from a hundred years ago and place them in an operating room today they would be lost. The practice of medicine has drastically changed to encompass the advancements and breakthroughs that have been made with science and technology. Justice Abella then went on to suggest that if you were to take a lawyer from a hundred years ago and place them in a courtroom today, they would need a bit of time to get caught up on the new rules of civil procedure but ultimately would be able to run a trial. I think this analogy speaks volumes as to how slow the legal profession has been at evolving and I contend that this issue is one that spreads across all facets of the practice of law. Moreover, law schools are a great starting point for which this problem could be addressed, yet little is being done.

Law schools are responsible for teaching and molding the minds of future lawyers, and yet for the most part they perpetuate outdated teaching methods. Of the law courses offered at TRU less than ten percent offer some sort of hands-on practical approach to teaching law. With that being said, none of those hands-on courses are black-letter-law courses nor are they required courses. Take the required courses of contracts law or civil procedures. A student can go a whole course learning about the tests and theoretical underpinnings of the law without ever learning how to apply it in the real world or have any practice drafting a legal document. Unfortunately, this is not an issue that is distinct to TRU Law; it is bolstered for the most part by all Canadian law schools.

Some may argue that articling is there to teach law students the practical aspects of the law. I would analogize that the articling process is similar to having taught someone the theory of how to swim and then throwing them off the deep end into water and demanding they swim. Of course, in British Columbia, articling students are assigned a principal as a sort of safeguard and a 10-week professional lawyer training course (PLTC) as a buoyancy aid, but it does not take away from the fact that there is a steep learning curve in the first few months of articles that law school does not prepare you for. There are also few mechanisms in place to assert the quality of education that is being received through the student’s articles. Comparing law to medicine, once again, medical students unlike law students are very well prepared by the time they graduate and do their residency. Medical students get a lot of hands-on experience throughout their medical education. Starting in their first year, medical students work with cadavers and then eventually work their way up to real patients as they do their supervised clinical clerkships in their third year. It would be absurd for medical students to learn exclusively through textbooks and lectures and only see their first patient upon starting their residency, yet for some reason it is well accepted that most law students will not draft a legal document or meet with a client until they graduate and start their articles.

I would suggest that law students are not only receptive to the idea of change but that they crave it. For example, this year at TRU’s student-run conference, the conference committee is taking the initiative to host a workshop on drafting corporate commercial contracts. I acknowledge that change is not likely to occur over night, however I believe this is a conversation that needs to be had. Modernizing how law is taught is the first step in the evolution of the legal practice.

I love the coinage “EvoLAWtion.” Very nice. The comparison to medical school is very interesting. My sense is that they are far ahead of law school in terms of developing practical problem-solving skills, adopting innovative learning methodologies, and paying attention to the evidence about what works to enhance student learning – but that medical school also has some of the features we know so well, like resistance to change and perpetuation of entrenched models largely because they’re what has been done in the past. Here are a couple of links on medical education that you might be interested in: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4795492/ and https://med.stanford.edu/news/all-news/2012/05/professors-propose-lecture-less-medical-school-classes.html

I wholeheartedly agree with you Emma. I have often thought about the fact that even after 3 years of law school,I do not feel prepared to actually practice law in the physical sense of the word. I love learning and I have tried to soak up all of the knowledge provided to us by our professors and the speakers we are privileged to have visit us, but I still feel wholly unprepared to draft contracts or speak before a judge. It was for that reason that several students and I organized the inaugural Environmental and Human Rights Law Negotiation. The preliminary thinking is that law school carefully establishes the knowledge base and it is from this base that we will be able to successfully practice law and be strong advocates for our clients. But, do our clients not deserve the very best from us? I believe they do, as I’m sure many of us do. That being said, I think being the best advocates we can be involves us having a more practical education. As more students weigh into this conversation and provide their insight and opinions, change will occur. As you stated above, the conversation needs to commence for this change to occur.

An issue to remember, however, is that the breadth of law is so wide. With so much to learn in any given course, whether it’s contracts, civil procedure, or real estate law, how does one justify redacting the course syllabus to allow time for actual practice. While I cannot posit a resolution to this issue, this is a dilemma that I foresee will stymie “evolawtion.”

Also, I think it’s important to remember that lawyers are said to practice the law. This invites us to be aware that from the time we begin articling to when we are called to the bar and beyond, we will never be experts; instead, we will always be practicing and, therefore, learning and improving our skills as lawyers. To me, this means that we have the support of the legal community to swim once we’re thrown into the deep end of the pool. They are beside us acting as our floatation devices while we learn the actual practice of law.

Emma, you raise many important points in your blog post. We do indeed need to reimagine and change legal education to ensure that students are in fact prepared to serve the legal needs of society and increase access to justice. After the first year of a regular law school education, which will ensure that students have learned fundamental skills, the second and third years should definitely be geared towards more practical and hands-on learning.

Many theoretical courses that are currently required in upper years can easily be offered as online modules. The time and resources that would be saved by this change could then be used towards creating more clinical opportunities for students. Law professors and practicing lawyers would then mentor upper year students, while they worked on actual case files and helped community members address their legal issues.

Learning would be more project-based, and students would feel a sense of accomplishment by addressing real world issues. By applying their learning to actual legal cases, students would also learn and retain concepts better. This would help support the dual purpose of providing practical learning for students and helping ensure greater access to justice. While law schools do currently offer some clinical opportunities, there is potential for even greater opportunities and a total shift in how the upper year curriculum is structured.

I totally agree with you, Emma! Law students definitely need more practical and hands-on experience to better prepare us for legal practice. I also agree that “modernizing” legal education would be a great starting point. Based on all the discussions we have had in L21C, it is quite evident that the legal profession’s resistance to change is a very big issue, and I’m glad that we have this open forum to discuss it.

Salona, and Japreet also bring up some important points. How would this practical or clinical component fit into our current curriculum? Should we be adding a 4th year to the J.D. program or should we be re-arranging the structure of the upper year curriculum? I agree with Japreet’s point that the 1st year of law school should allow student’s to learn the basic and fundamental skills, as it currently does. The 2nd and 3rd years leave room for more change. I definitely think that this practical component, in whatever form it takes, should be mandatory. Like you mentioned, less than 10% of courses at TRU offer some sort of practical experience. But those courses may also have a limited class size. I think it’s really important that every law student gets an opportunity to gain practical/clinic experience, and making it a mandatory credited course would ensure that.

Oh god, no fourth year of the JD program!!!!

As a counter point to this, I have gone to an event that had a few of the professors from our faculty, and when it was brought up that some practitioners complained about the lack of practical experience that law school students came to their practice with, a professor who-shall-not-be-named made what I thought was a good point: they said that a lot of practitioners bitch about students not even knowing how to do really basic forms for example, but that those were a really basic and repetitive thing that the student would do many times while articling and in their careers, and that rather than learn a repetitive basic task that could be learned quickly after school, the real value of law school was that it was the only time in their entire career that students would have a chance or THE TIME to learn the reasons of legal thinking, how the law had developed, and why it was the way it was.

Filling out forms and basic practical skills are great, but I agree with that professor that there will never be a time when law students will be able to explore the “why” of law, and chase ideas down rabbit holes and play with ideas of law. When you are being paid by in 6 minute increments, they don’t pay you to ask questions of “why” about law, or to chase questions or ideas that you may have. You will spend the majority of your time just doing practical work that gets to answers and results, so why not spend your law school career learning and asking questions you won’t have time for later?

I completely agree, and I think part of the problem when we talk about “practical training” and “practice-ready law students” is that we often mean really different things when we use those words. The micro skills, like completing particular court forms, in my opinion have no place in law school. They’re easy to learn, they change all the time, and they are pretty rote tasks. I think there is a version of “practical” that does have a place in law school and that there is probably not enough of. It is hard to describe exactly, but I am thinking really of inculcating a mind-set or habits of thinking: approaching legal problems as a lawyer thinking about the practical needs of their client, as opposed to as an abstract, philosophical or intellectual problem. The abstract, philosophical, intellectual approach is naturally part of academic legal education, but I do not think it is a good thing to get only that. To put it in more concrete terms, I think it does law students a real disservice if they graduate with lots of training in writing 40-page academic papers about legal issues, and no training in writing brief, economical memos on legal issues which are more like the work product clients need. And the ways of thinking about the problem that lead to those two outputs are very different.